Heavy Hydrocarbon Fingerprinting

Nov 9, 2020

Often in the compositional analysis of petroleum condensates the analysis only quantifies the lighter compounds while leaving the heavy components as bulk “plus fraction”. Properties such as molecular weight and relative density are then assigned to the plus fraction of a sample. This is not a problem in gas samples where the plus fraction may make up less than 1% of the total sample. However, in condensate samples the plus fraction commonly makes up 50-80% of the total sample. Typically, the plus fraction starts at n-Heptane (nC7) or n-Decane (nC10) and can continue until C100.

Other analyses are required to speciate the components in the plus fraction, but these tests tend to be relatively expensive. This brings us to the purpose of this post: can we use machine learning to model petroleum plus fractions? At first glance it might seem unreasonable to try and predict over 30+ compounds from a small dataset and only a handful of input compounds. However, you will see the problem is relatively constrained, as explained in the background section of this post.

Background

The “fingerprint” of an oil sample is the full chromatographic profile of the oil that results from analysis by a GC. While the full composition of the oil can be determined by one chromatograph run the sample usually must be ran (at least) twice to be fully quantified: once to determine the concentration of the light ends and again to determine the concentration the plus fractions.

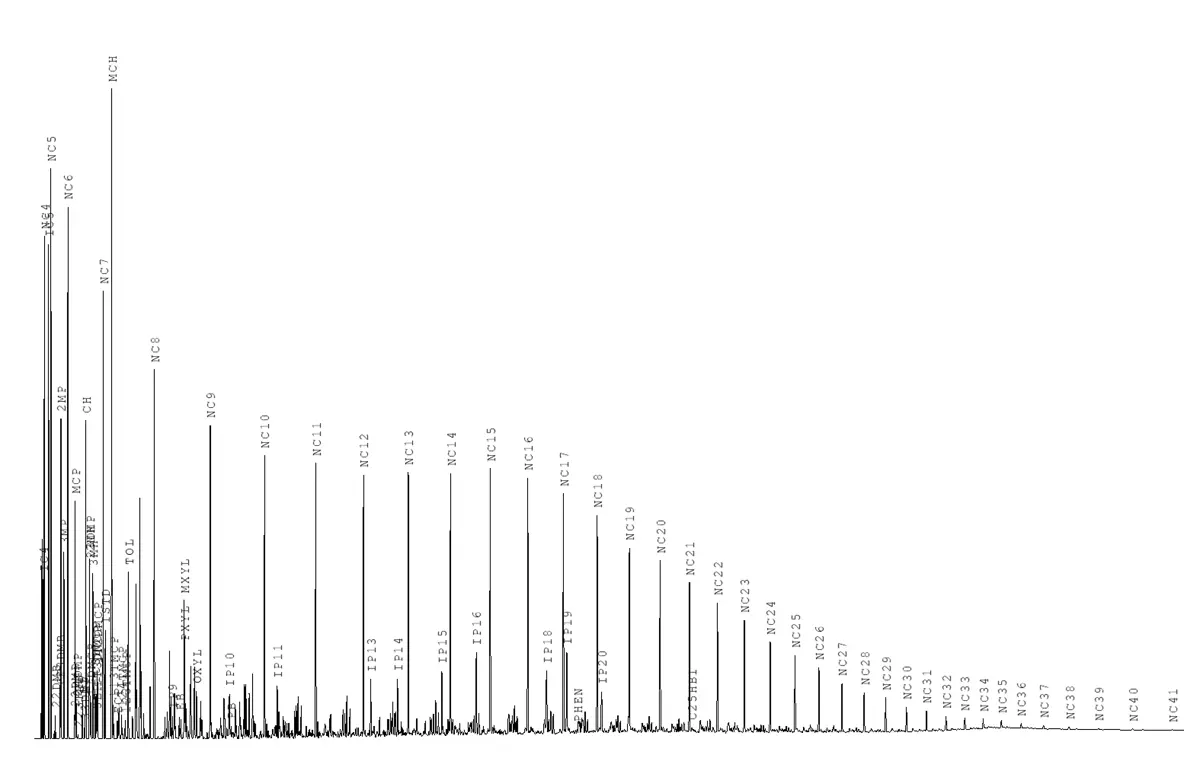

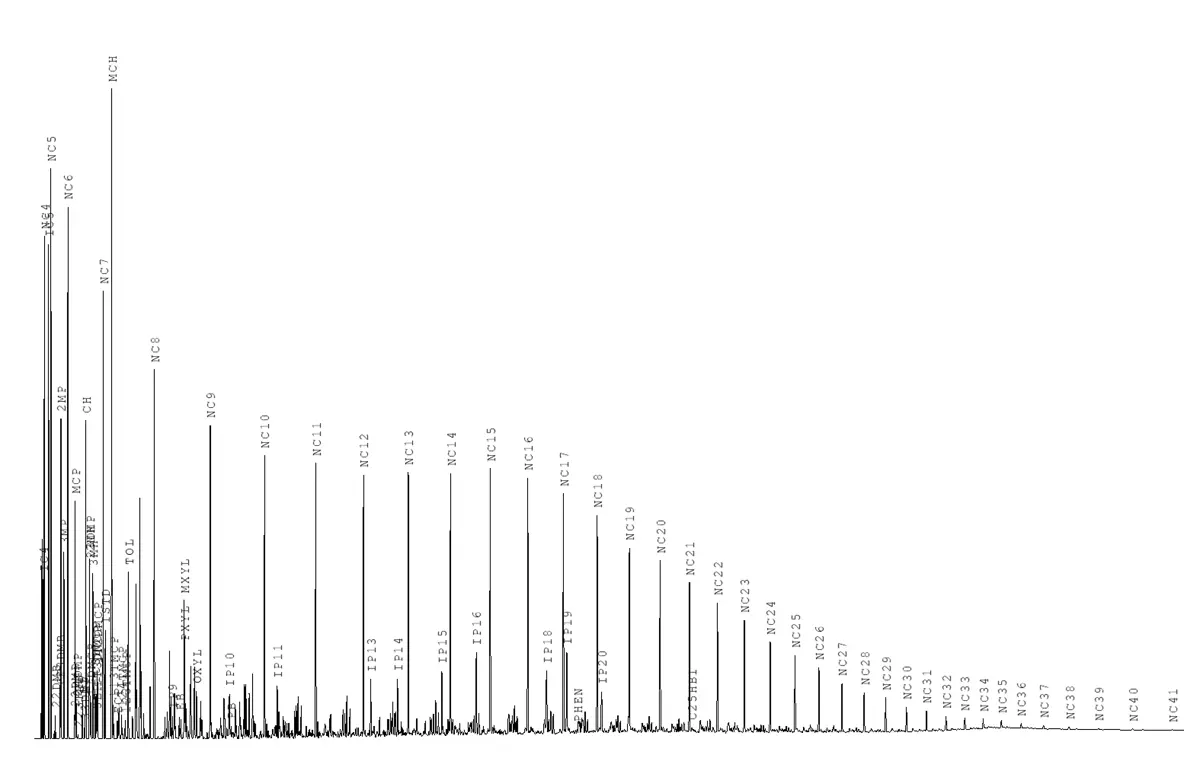

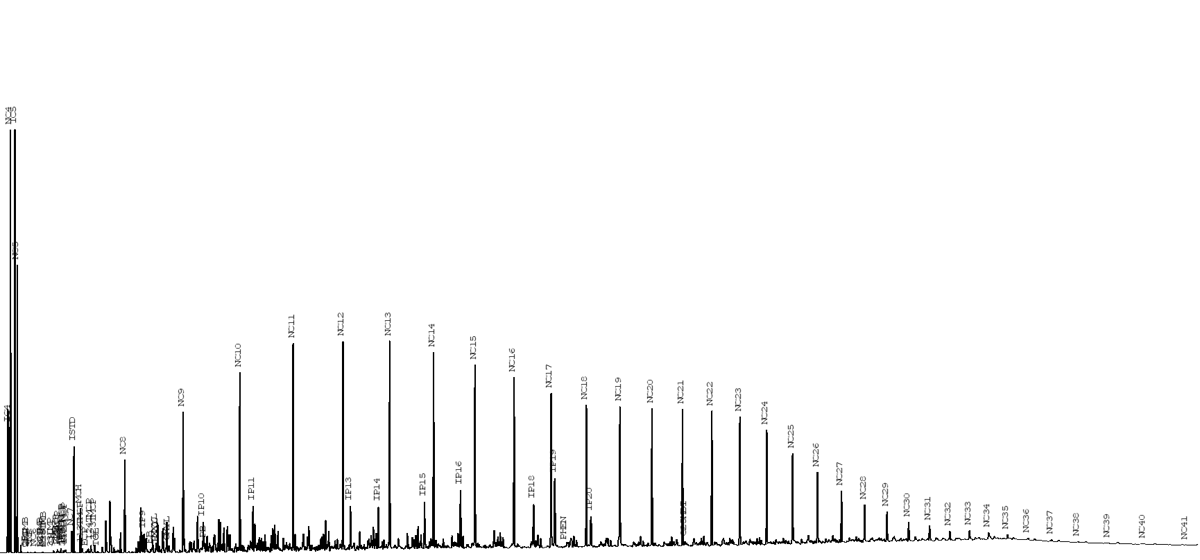

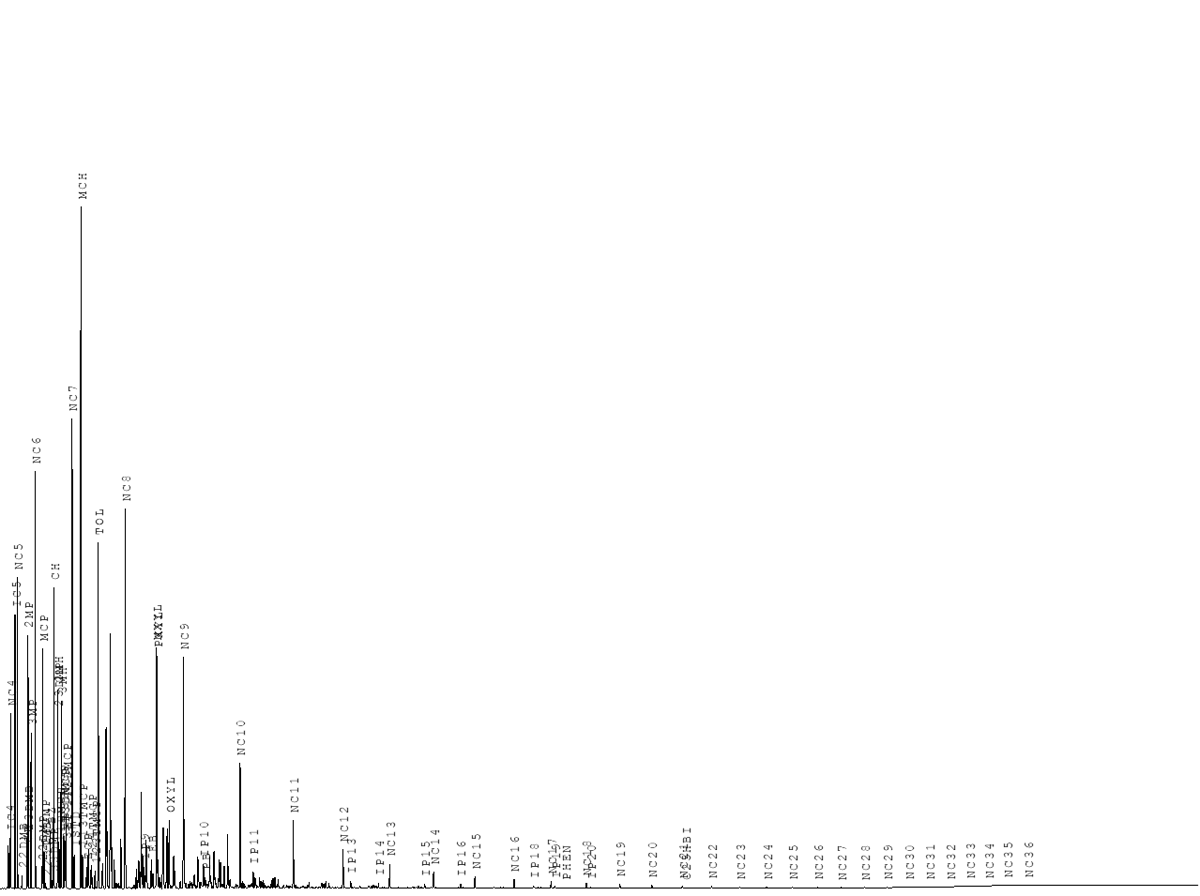

Fingerprint Example

Oil alternation affects will change the shape of the fingerprint of the samples. These affects include thermal alteration, biodegradation, water-washing, gas-washing, deasphalting, devolatilization, thermochemical sulfate reduction, contamination, and sampling issues (Dembicki 2016). In this post I will only focus on thermal alteration of the oil since it has a high impact on the oil sample’s plus fraction. Also, the data I had access to did not include Pristane and Phytane biomarkers, so it would be very hard to determine if any samples showed signs of biodegradation.

Thermal alteration or “oil maturation” happens at elevated reservoir temperatures and breaks down heavier hydrocarbon molecules into lighter compounds. This process exists on a continuum from the least mature oil to very mature oil. The least mature oil will have large amounts of heavy ends and display more of a multimodal Poisson distribution. The very mature oil will follow more of a typical Poisson distribution having low concentrations of heavy ends.

Low Maturity Oil

Very Mature Oil

Modeling and Results

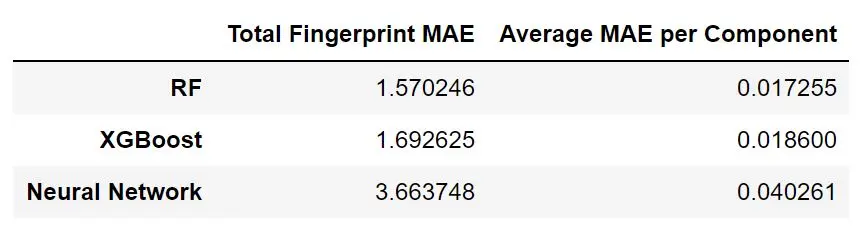

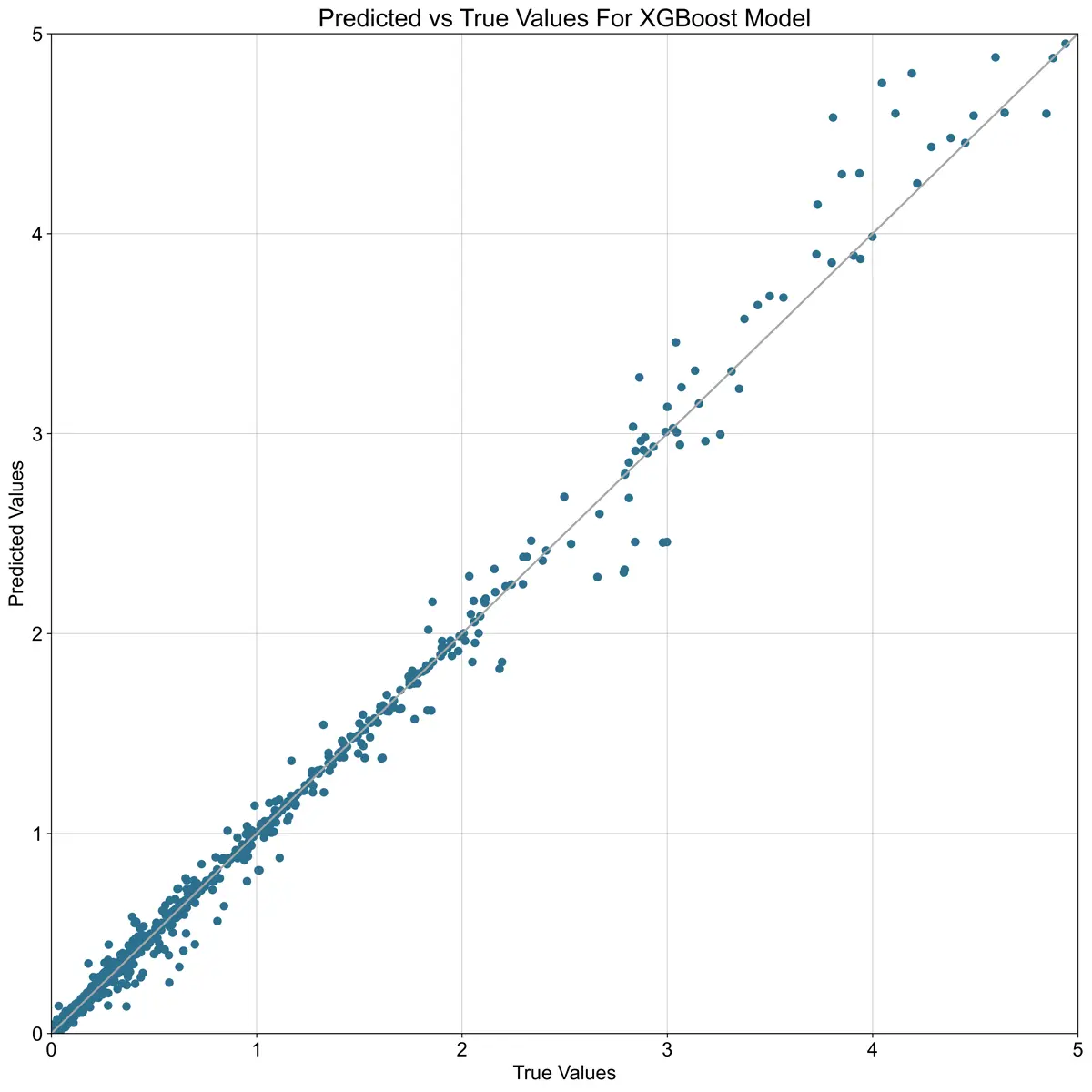

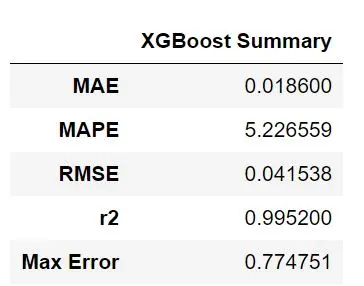

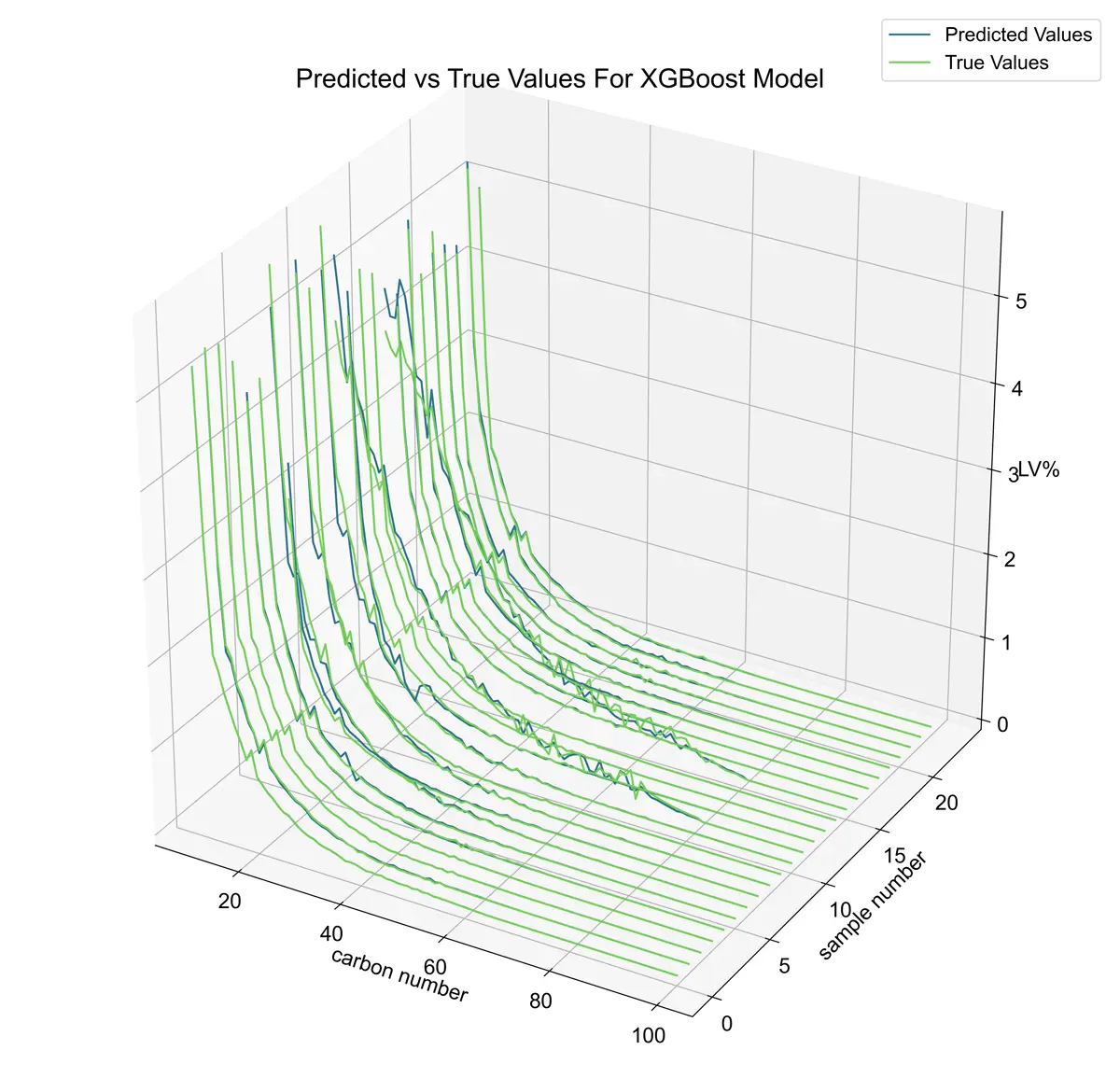

The dataset for this model was small. It only consisted of just over 100 samples. I tested a few models, but XGBoost and random forest performed the best. It outperformed the neural network significantly, likely because of the small dataset size. Since the results of the random forest model and XGBoost were close, I decided to stick with XGBoost for the rest of my testing. Some results are shown below.

Model Comparison Table

XGBoost Results

XGBoost Summary

XGBoost Model Examples

Conclusion

I acknowledge that I did not have much data for this model and most of the oil was in the moderately mature to very mature range. Since I am only looking a narrow section of possible oil types, the model would most likely perform poorly on a low maturity oil. However, re-training with a larger dataset could address some of these shortcomings.

References

- Breiman, L. 2001. Random Forests. Machine Learning 45(1) 5-32. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/a:1010933404324

- Chen, T., and Guestrin, C. 2016. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY. 785-794. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

- Dembicki, H. 2016. Practical Petroleum Geochemistry For Exploration and Production. Cambridge: Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803350-0.00004-0

- Koul, A., Ganju, S., and Kasam, M. 2019. Practical Deep Learning for Cloud, Mobile, and Edge: Real-World AI & Computer-Vision Projects Using Python, Keras & TensorFlow. Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media.

- Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V., Vanderplas, J., Passos, A., Cournapeau, D., Brucher, M., Perrot, M., and Duchesnay, E. 2011. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, Vol 12: 2825-2830.