Equations of State Modeling With Neural Networks

Jan 20, 2020

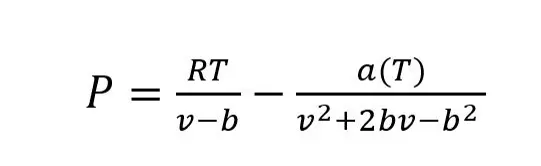

Complex equations, such as “Equations of State” (EOS) are used extensively in the oil and gas industry. They are used for calculating thermodynamic properties such as bubble point, gas to oil ratio, and shrinkage, among other properties. However, the top EOS can take quite a while to run. This got me thinking: could neural networks be used instead of EOS to speed up calculations? Neural networks are commonly referred to as universal function approximators, which means they should be able to model complex equations like the EOS. I based the machine learning models on results from the Volume Translated Peng-Robinson EOS (VTPR EOS) with Gibbs free energy mixture parameters to provide the most accurate model.

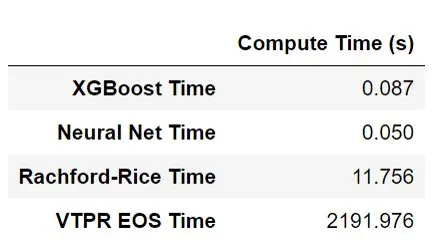

Computation Time

The real value of using machine learning here is not accuracy but computation speed. The machine learning models can do phase calculations incredibly fast compared to traditional methods. The table below shows a time comparison for each method when calculating results for 1000 samples. For the machine learning models, I used XGBoost and a neural network. They were 3–4 orders of magnitude faster than the traditional engineering equations. The VTPR and Rachford-Rice calculations could be sped up slightly with improvements to the optimizer. However, they would still be orders of magnitude slower than the machine learning models.

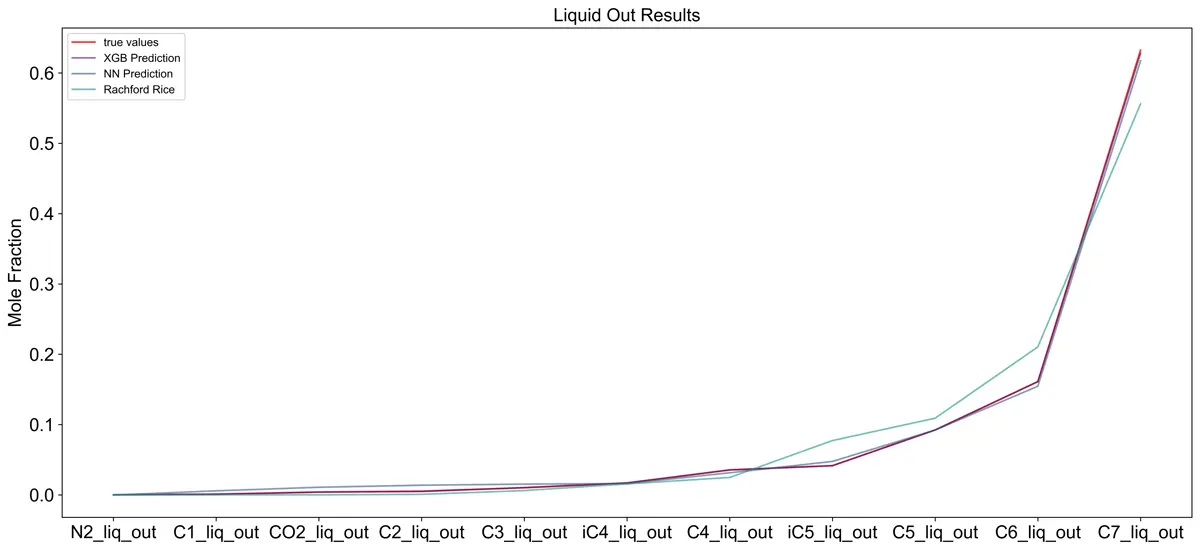

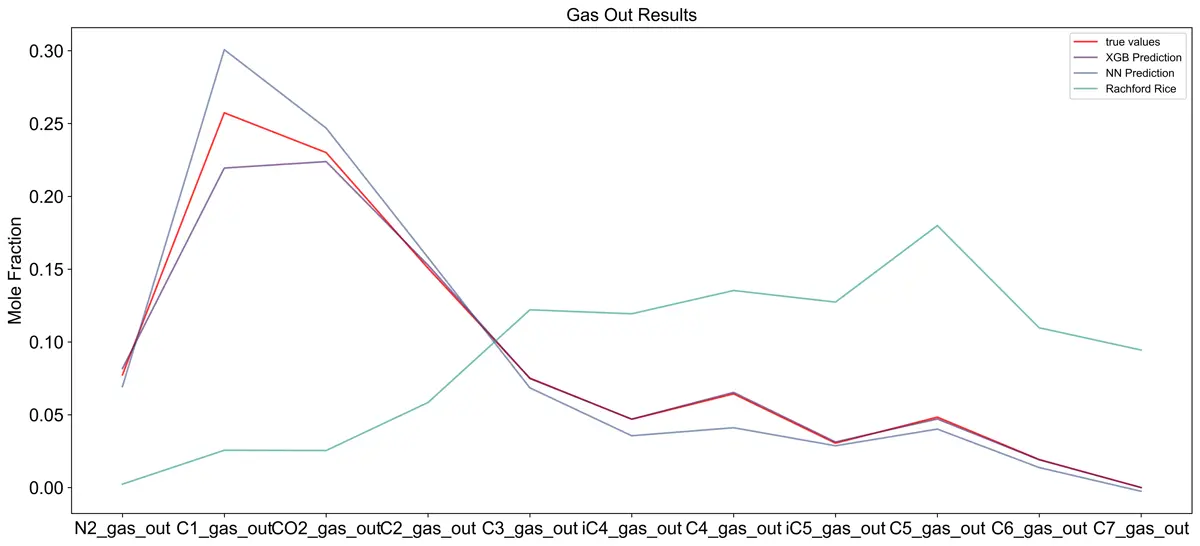

Model Accuracy

Since the equation of state results are the objective function for the machine learning models, I also used the Rachford-Rice equation to compare the neural network results. The Rachford-Rice equation is much simpler than the VTPR EOS and runs much quicker due to fewer convergence loops. This gives it a closer compute time to the machine learning models. The results below show that the Rachford-Rice equation (green) provides decent results for the liquid fraction but poor results for the gas fraction. Both the XGBoost model (purple) and the neural network (blue) outperform the Rachford-Rice equation in this example.

Example Composition Outputs From One Sample

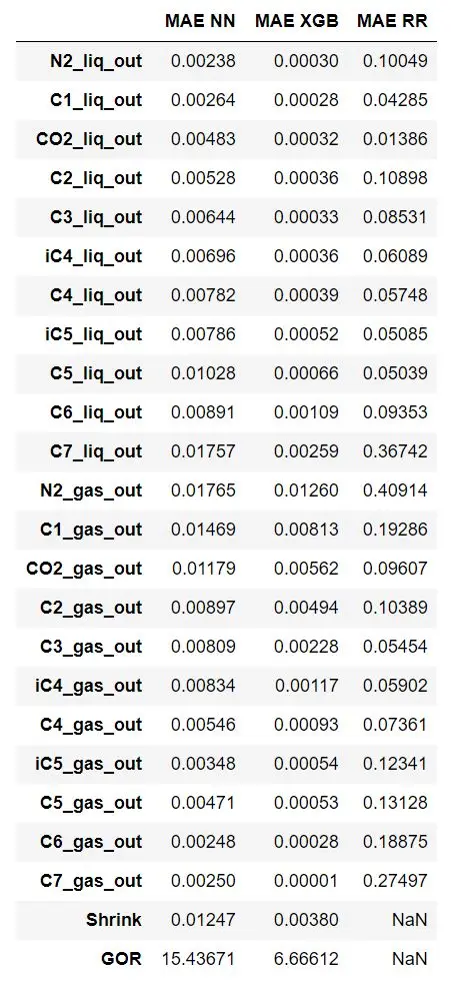

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of Every Component For Each Model

NN = Neural Network, XGB = XGBoost, RR = Rachford Rice

Data and Model Creation

The main challenge for this problem is generating a sufficiently large training set for the neural network. First, I need to generate data representing actual oil/condensate samples and then run those samples through the VTPR EOS. When I first approached this problem, I generated a random dataset based on normal distributions of each input. The downside of this method is that some compositions might not make sense as condensate oils. For example, you would rarely see a condensate sample with high methane and ethane but low pentanes. I am basing a lot of the ideal condensate compositions on my own experience working with these samples.

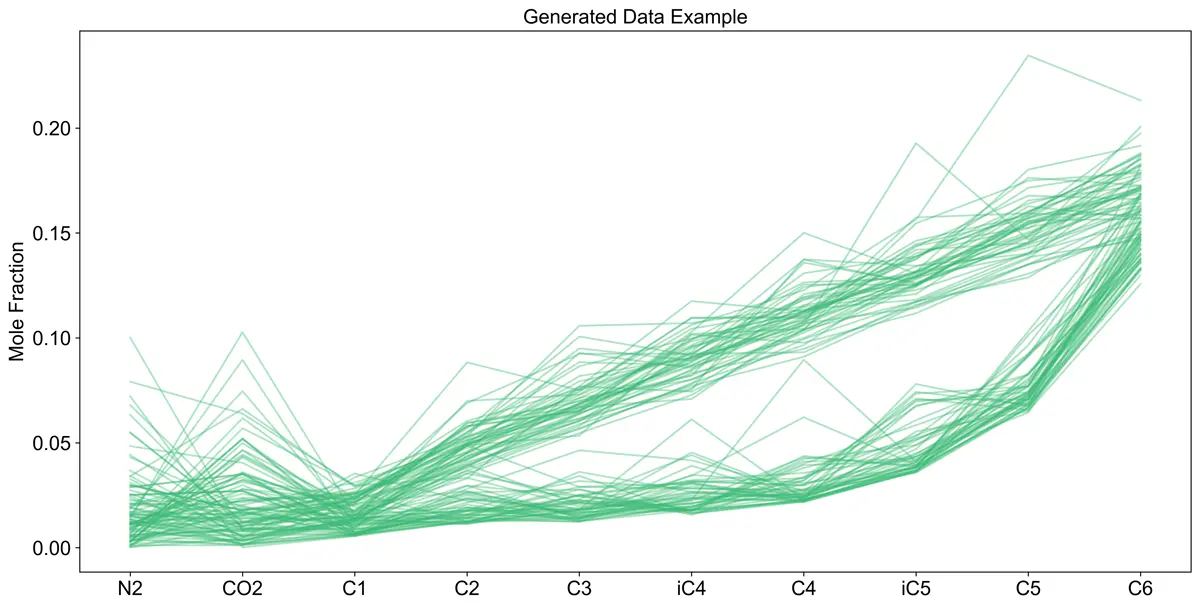

From here, I pivoted and used random linear and exponential equations (from C1–C6). The remainder was then added to the C7+ fraction, so the total mol fraction was equal to 1. Random noise was then added to each component and other input values like temperature and pressure. The equations to generate the data could be further improved, but that is outside of the scope of this post.

Once the dataset was created, it was time to crunch some numbers. I fed 100 samples into the VTPR EOS model and quickly realized this was going to take a while. The 100 samples took about 5 minutes to run using the VTPR EOS model. To speed up the process, I implemented multiprocessing and used 10 cores for the calculation instead of 1. This gave me effectively 10 instances of the code running in parallel, which sped up the process. After multiprocessing was in place, I ran all 100,000 samples, and they took around 8 hours to finish calculating. Now that my training data was fully generated, the machine learning models can be trained.

Examples of the Generated Data (200 Samples)

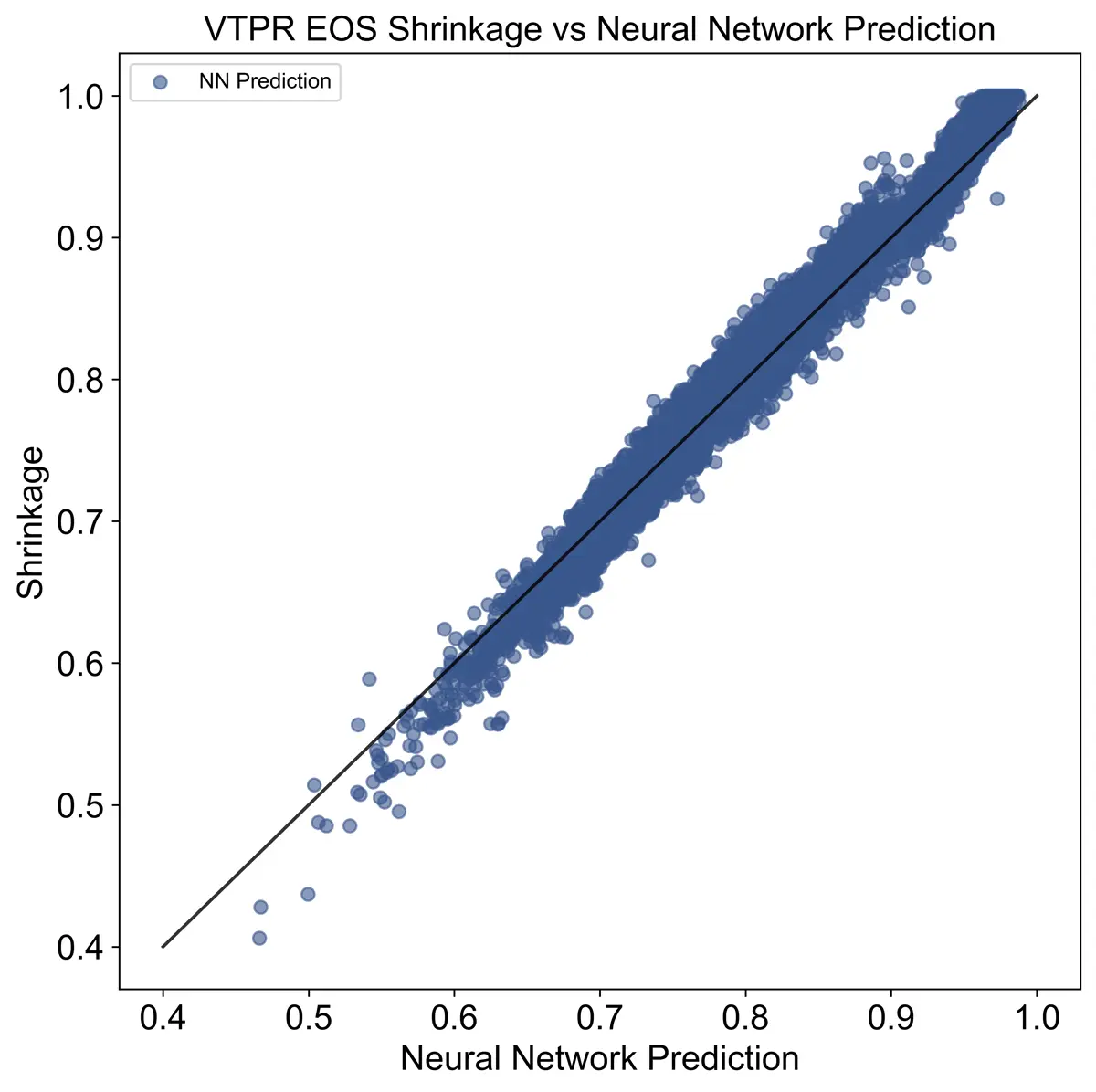

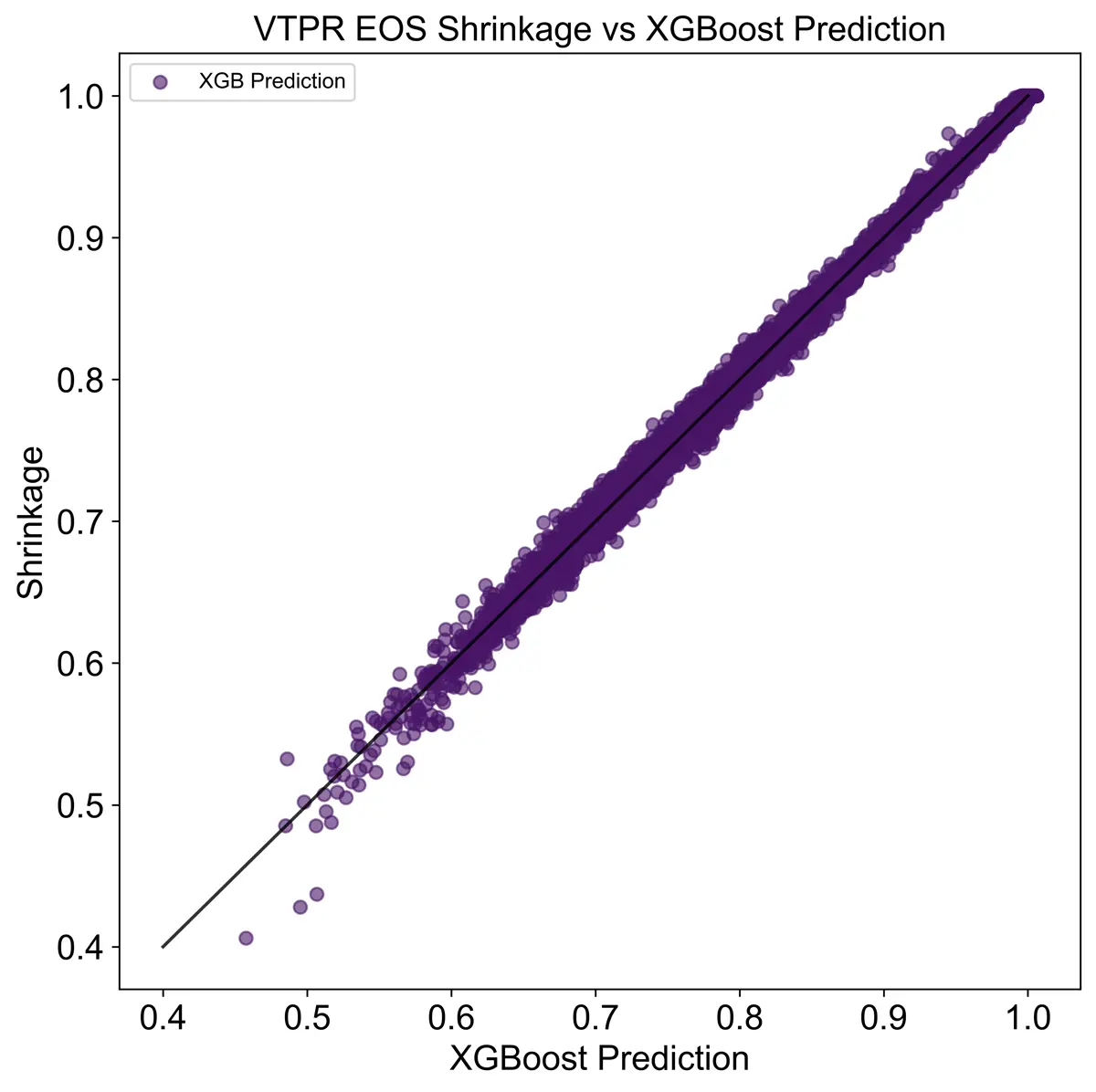

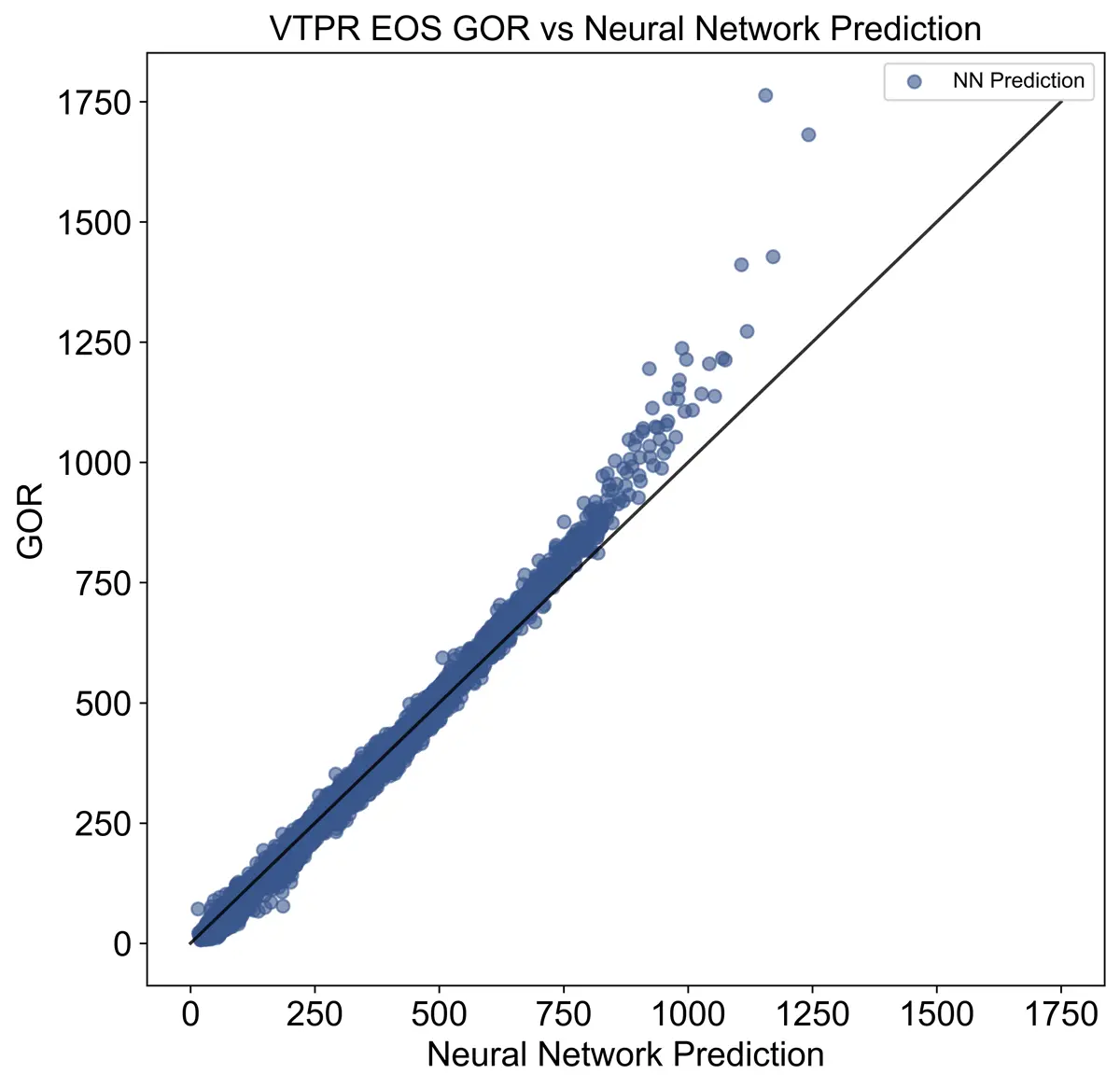

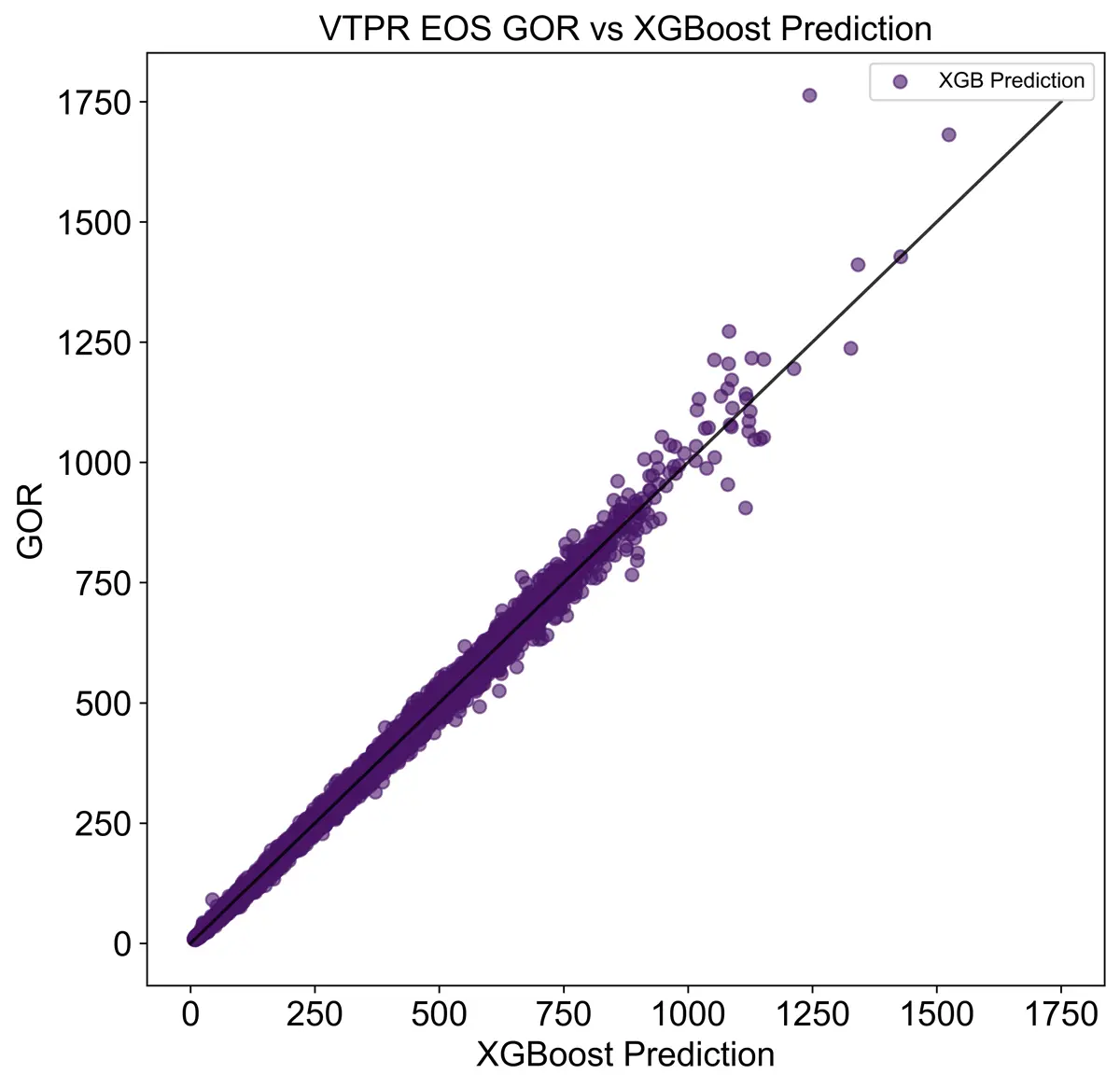

Shrinkage and GOR are also key values obtained through the VTPR EOS, so I modeled those with the machine learning models alongside the output compositions. Both models performed fairly well as seen below.

Shrinkage and GOR Accuracy

Conclusion

The machine learning models were able to predict thermodynamic properties relatively well while decreasing computation time by over an order of magnitude of 4. The machine learning models' accuracy could be further improved by using more advanced machine learning techniques and increasing the amount of training data. With this method creating more training data is easily done by running generated compositions through the VTPR EOS. Furthermore, more representative datasets could be generated if the user has access to real oil and gas compositional data. When fast equations of state computations are needed, machine learning models trained on representative data should be employed.

References

- Abudour, A. M., Mohammad, S. A., Robinson Jr, R. L., & Gasem, K. A. 2013. Volume-translated Peng-Robinson equation of state for liquid densities of diverse binary mixtures. Fluid Phase Equilibria 349: 37-55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluid.2013.04.002

- Chen, T., and Guestrin, C. 2016. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY. 785-794. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785

- Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M., and White, H. 1989. Multilayer Feedforward Networks are Universal Approximators. Neural Networks, Vol 2: 359-366. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(89)90020-8

- Kandula, V. K., Telotte, J. C., & Knopf, F. C. 2013. It's Not as Easy as it Looks: Revisiting Peng—Robinson Equation of State Convergence Issues for Dew Point, Bubble Point and Flash Calculations. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 41(3): 188-202. doi:https://doi.org/10.7227/IJMEE.41.3.2

- Rachford Jr, H. H., and J. D. Rice. 1952. Procedure for use of electronic digital computers in calculating flash vaporization hydrocarbon equilibrium. Journal of Petroleum Technology. doi:https://doi.org/10.2118/952327-G